Figuring out the number of calories in a meal could soon become as simple as pushing a button, thanks to a new calorie-counter machine GE is developing with Baylor University.

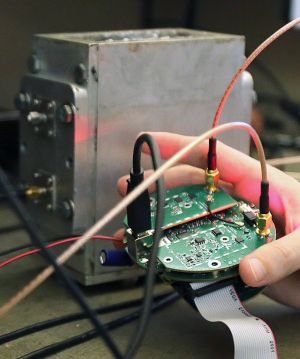

The company has been working with Baylor University’s electrical and computer engineering department for the past two years on developing the device. The prototype uses low-level microwave pulses to measure the water and fat content in food to calculate calories.

Though the device uses microwaves, it will not cook or heat food.

So far, the machine has been able to successfully determine the caloric content of simple liquid mixtures of water, oil, sugar and salt. The trials have tabulated the calories in the mixtures with a 90 percent to 95 percent accuracy.

But a marketable calorie counter that could be sold to consumers is likely three to five years away from being a reality as researchers still must figure out how to apply the technology to solid foods, said Matt Webster, GE senior scientist in diagnostics, imaging and biomedical technologies.

“This is a high-risk, high-payoff kind of project; in other words, this is a hard project,” said Randall Jean, Baylor associate professor of electrical and computer engineering. “It’s not something that’s really simple to do, but if we do it, I think everybody’s going to want one. All of us are trying to evaluate what this idea is worth and how much it will cost to take it to completion . . . all these pieces have to come together.”

Idea’s origin

Webster came up with the idea for the machine a few years ago after his wife said she would prefer to have a device that automatically calculated calories in her food instead of digital-activity monitors that were being marketed and sold to consumers.

He made some progress during an innovation competition at GE. Through analyzing nutritional data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Webster discovered that the amount of fat and water content in a food item were the most vital indicators for measuring calories.

GE researchers determined that protein, fiber and simple and complex carbohydrates collectively account for 3.8 calories per gram of food, a formula that is weighed in the calorie machine’s calculations.

“We want to take a measurement area of a plate of food and we want the average over that whole area and get just the water and fat content,” Webster said. “There’s a lot of physical problems to overcome, but I’m thinking more simply, that what we really need is a generic average . . . no matter what you put on the plate, what’s the total of the whole plate?”

But the company needed a vehicle to measure the water and fat, deciding that microwave technology could be an effective application. Webster sought out Jean, who invented a guided microwave spectrometer that GE thought would accomplish the machine’s goals.

Before coming to Baylor, Jean spent 17 years heading technology startups that used microwave-sensing technology to develop measurement and control tools and processes for industrial companies.

When electromagnetic waves enter any material, that material will either store or dissipate the energy. Jean said water stores a lot of the microwave energy while fat doesn’t, and by measuring the amount of energy stored as the waves pass through food, you can determine the percent of each present in the item.

“I thought it was a great opportunity,” Jean said of the partnership. “I thought what they’d come up with was pretty novel, and that people would care about it. And plus, as a Baylor professor, I’m always looking to get research dollars in my lab, so GE turned out to be a good partner.”

Jean and his research company, Rhino Analytics, received a patent in 2006 for a new pulse-dispersion network analyzer, which builds on the microwave measurement capabilities of the guided microwave spectrometer but can be manufactured at a significantly lower cost.

Brandon Herrera, a graduate student who will receive his Ph.D. in electrical and computer engineering this December, has spent much of the past six years building the device and software from scratch. That hardware is being utilized in the calorie-counter machine.

“It’s fun to actually be able to make a difference,” said Herrera, 28. “Electronics by themselves is just, ‘OK, it’s just math.’ But it’s fun to be able to apply it to something that people will actually need and can use.”

Hundreds of trials

Robert Marks, distinguished professor of electrical and computer engineering at Baylor, has assisted in analyzing the data from the test trials of the liquid mixtures for the calorie machine. Hundreds of trials were conducted to fine-tune the methodology and ensure that the results would remain consistent with repeated demonstrations.

“It’s significant (research) because of the obesity epidemic,” Marks said. “Hopefully with one of these calorie counters and some self-discipline and some exercise, that sort of thing can be addressed; that’s what we’re hoping. And I know that there’s a demand, because my wife said, ‘I want one! I want to buy the first one!’ ”

The next challenge will be developing a means to measure water and fat content in nonhomogenous mixtures. GE and Baylor will begin doing tests on soup mixtures first before moving to solid foods and full meals.

Webster said he hopes that some success in measuring soups will lead to the creation of a machine that could be marketed to restaurants and food producers to help them determine calories in meals. GE may be able to market an industrial product in which a meal could be blended into a liquid to measure the nutritional content with the next two years, he said.

The FDA has been pushing for restaurants to include nutrition information on menu items as part of national pushes to curb obesity.

“It’s harder for smaller restaurants to comply with that, especially independent restaurants that change their menus a lot,” Webster said. “Having something where you can measure the calories quickly will allow you to have a special of the day where you can just make (a menu) up and have a reasonable calorie estimate.”

Webster said because the calorie counter will take so much time to reach final development stage, having a university partner for the research helps keep the project moving forward as GE may opt to divert resources to other products that may yield quicker returns on investment.

“It’s such an early-stage project, we’re talking three to five years out, that the science is really partly in the academic center right now, and it’s harder for a large company to have patience for that kind of stuff,” Webster said. “They want this thing out now. I want this thing out now, too, but there’s still a lot of work left to be done, and I think there’s a good place for academic collaborations in a project like that.”

Once a final product is sold on the market, GE, Baylor and Jean’s Rhino Analytics will share royalties based on the respective intellectual property each entity provided.

Jean’s startup company also plans to explore ways to manufacture and market products to industrial companies that utilize the pulse-dispersion technology.

“Being an engineer, engineers want to make things that change people’s lives,” Jean said. “A pure scientist like a physicist or a chemist is happy just knowing that they’re revealing new truth. Engineers always want to make something.”

Yesterday & Today

Yesterday & Today

GreenLife Nursery and Landscaping

GreenLife Nursery and Landscaping